Glaciers have historically determined the boundary between Italy and Switzerland in the Alps. Now, their melting has led the two countries to redraw a small section of their border over the past year and revived concerns of how climate change might impact mountain communities around the world in the coming years.

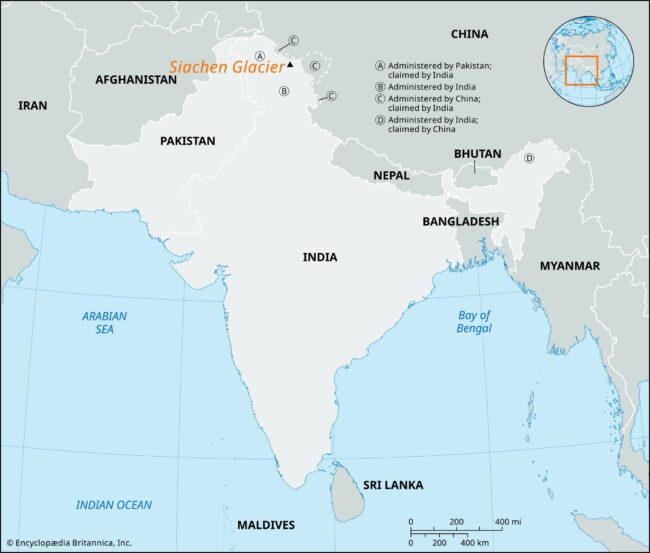

Glaciers form the borders of many countries—ranging from those in the Andes that separate Chile from Argentina to the Siachen Glacier, which marks the northern point of the Line of Control in the disputed Kashmir region between India and Pakistan. Glaciers in the Alps define the borders between Italy and a number of countries, including Switzerland and Austria.

However, climate change is leading global temperatures to rise, and high-mountain areas are warming even more rapidly than the rest of the planet, with temperatures in the Alps rising twice as fast as the global average. Because of increased glacier and snow melt, many of the borders established by natural features for centuries no longer align with those features, sometimes fueling intense border disputes between nations.

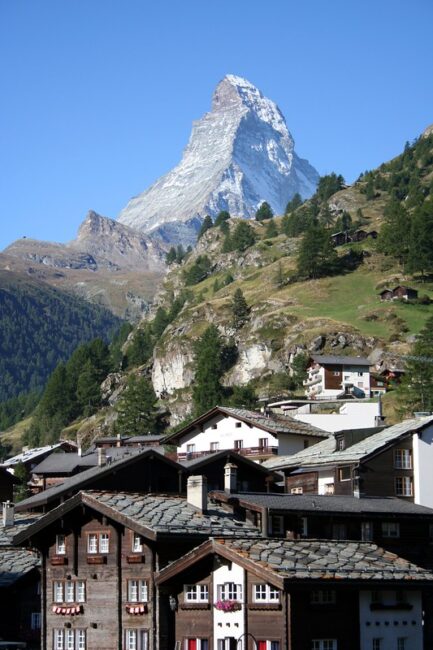

In Switzerland and Italy, large sections of their shared border are marked by glacier peaks and snowfields in the Alps. Recently, these countries have watched as the glaciers on Matterhorn Peak—one of the tallest mountains in the European Alps and home to the world-famous Zermatt Ski Resort that receives over two million visitors per year—have continued to melt. For many decades, the ridge formed by the highest point of these glaciers marked the border between the two countries. However, climate change has shifted this ridge slightly toward Italy.

In May 2023, Italy and Switzerland worked together on an agreement to redraw their border to reflect these changes, shifting a small section of their border farther into Italian territory. This past October, the Swiss government officially approved the change and the process for approval is currently underway in Italy. Once it is approved by both countries, the changes to the border will become official.

Unlike many border disputes, this redrawing has been fairly amicable and with little fanfare from either country. Adrian Brügger, a Swiss professor in Civil Engineering at Columbia, says this is likely due to the nature of European countries and borders. “There’s a very relaxed attitude toward borders, especially in border areas,” Brügger said in an interview with GlacierHub, adding that people don’t mind the change since “the border is the top of the mountain, and the top of the mountain has moved.” Though Switzerland is not part of the European Union, both Italy and Switzerland are part of the Schengen Area, which allows for free travel between 29 European countries, reducing the significance of border changes.

Another reason for the lack of tension, according to Brügger, is that the redrawn area is not private property. “The vast majority of mountains on both sides are what we call ‘allmend,’ which is communal-use public land. No one is worried about giving up their backyard,” he explained.

And as for the impacts to the skiing area and tourism industry in the region, Brügger points to the fact that Matterhorn and the Zermatt Ski Resort has already been a binational ski area for a long time, with mountain railways connecting to the resort from both countries. “The railways on both sides care about their ticket sales, and the border moving a few meters doesn’t change those,” he said. “They’re probably more scared about the shortage of snow.”

The fear of losing snow highlights the underlying issue behind redrawing this border: mountain environments on both sides are becoming more hazardous due to climate change. In both Switzerland and Italy, melting permafrost is leading to rockslides that threaten communities and more frequent extreme floods. “There’s a fear of displacement in areas that have been settled with houses that are 500 years old. People just live with a go bag beside their bed,” Brügger explained.

Marco Tedesco, a Lamont Research Professor in the Columbia Climate School, who is Italian, spoke of this concern as well in an interview with GlacierHub. “This signals that even the most remote places in the world are contaminated by human actions. This time it was glaciers, but one day—or somewhere else—it is about food, migration and water supplies.” He added that while the redrawing of the border may seem mostly symbolic, it highlights the rapidly changing climate already affecting communities in these countries.

This recent shift is not the first time that Alpine countries have needed to redraw its border to reflect changing ice. In 2006, Italy and Austria signed an agreement to make their border a “moving border” to account for changes in the border-defining snowfields and glaciers once thought stable.

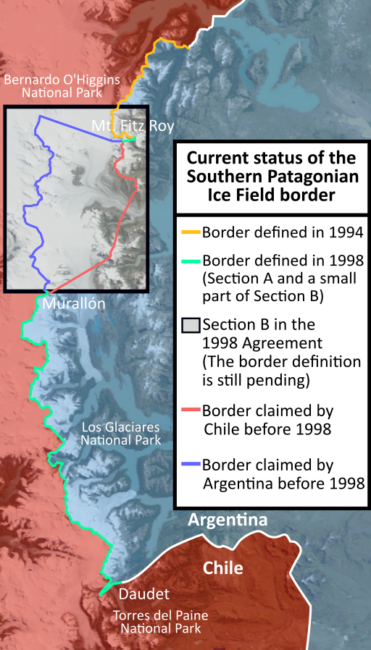

However, not all climate change-induced border conflicts have been so easily resolved. The border between Chile and Argentina within the Southern Patagonian Ice Field is still disputed to this day. An agreement between the two countries was signed in 1998, but one section of the border remains undefined as the countries have not reached an agreement.

An even more contentious dispute surrounds the Siachen Glacier in Kashmir, where India and Pakistan have fought on and off since 1984, making it the highest elevation battleground on the planet. A cease-fire was approved in 2003 with the line eventually becoming the Line of Control, but both countries maintain a military presence in the area and the border is still heavily disputed.

The redrawing of the Italian-Swiss border is just one instance that highlighs how climate change is affecting mountain communities and national borders. As glaciers and snowfields continue to shrink, these border shifts (both disputed and not) will become more common and living in these regions will be more hazardous. Countries with glacier- or snow-defined borders that have not yet faced this issue should begin to prepare for it. Solutions like the “moving border” that Italy and Austria created may be helpful for other disputes. However, depending on the relations and histories of the countries, this could be difficult, if not impossible.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel